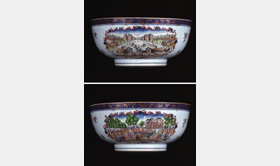

Topographical Punchbowl

Qianlong, circa 1790

English Market

Diameter: 16 inches (41cm)

Source: Cohen & Cohen

Download Full SpecificationBack to List...

A rare famille rose European-subject punch bowl with two foliate panels depicting the Foundling Hospital on one side and the 'Grand Walk' in Vauxhall Gardens on the other, the rim with iron-red and gilt grapevine on a blue ground.

This extremely rare bowl shows two views of London (The Foundling Hospital and Vauxhall Gardens) and may have been intended to pair another bowl with similar rim decoration and two other views of London (The Mansion House and The Ironmongers’ Hall, Fenchurch St). All these views date from around 1750 though the bowls were made at the end of the eighteenth century. The image of the Foundling Hospital was described by Beurdeley and Hervouet as being of Versailles; however it is now known to be of the Hospital after an engraving printed for John Bowles at the Black Horse in Cornhill, & Carington Bowles in St.Paul's Church Yard, London, c1760. The view of Vauxhall Gardens is taken from an engraving by Johann Sebastian Muller after a painting by Samuel Wale.

The Foundling Hospital was the creation of Captain Thomas Coram (1668-1751) a remarkable man who had been moved by the abandoned and dying babies that he saw on the streets of London. He had been a successful shipwright, founder of the first shipyard in Taunton, Massachusetts and a farmer there from 1694-1705. He was less successful as a farmer because he was disliked by the Puritans who conspired against him. On retiring to London he set about working for the foundlings with a tireless campaign that involved all of London society. This culminated in a Royal Charter (17 October 1739) granted by George II, whose wife Queen Caroline was a big supporter of Coram. The first children were received in Hatton Gardens on 25 March 1741 and there were moving descriptions of the wailing mothers departing their children.

The site was purchased from the Earl of Salisbury and money was raised by donations and concerts. Handel raised £7,000 from a performance of his Messiah. The building was designed by Theodore Jacobsen (ca. 1686-1772) and the artist William Hogarth (1697-1764) became a central figure and was appointed the first Governor of the Hospital. Together with the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack (1693-1770) he established an art gallery there, opening on 1 April 1747, with pictures donated by artists of the day, including Francis Hayman and Peter Monamy, for which the public paid an entrance fee and this money helped fund the Hospital. After Hogarth fell out with the St Martin’s Lane Academy, the Foundling Hospital became the prime site for the display of contemporary art in London and was inf luential in leading to the foundation of the Royal Academy.

The Foundling Hospital became a very popular cause and everyone important in eighteenth century society was involved. Having been built in an open area it had become surrounded by pollution by 1926, when the children were moved to Redhill, Surrey and then in 1936 to Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. The main building was demolished by a developer who planned to move Covent Garden market there, a plan which failed. The land was turned into a children’s playground, Coram’s Fields and today entrance is only permitted to adults if accompanied by a child. The gates have survived. The Foundling Museum occupies a nearby site at 40 Brunswick Square, where some of the keepsakes left with the babies can still be seen.

Coram himself was removed from the board after various arguments. He seems to have been a difficult and awkward man, of great humanity and an uncompromising moral certitude, which his contemporaries found uncomfortable and admirable in equal measure.

Vauxhall Gardens seems a very different place, a social whirl of hedonistic pleasure and entertainment. Their high period of popularity was under the management of Jonathan Tyers (1702-1767) who reopened them in 1732 with a splendid Ridotto al Fresco attended by Frederick, Prince of Wales. A major driving force behind this was William Hogarth who is believed to have planned the opening himself.

Admission was one shilling, a price that remained constant until 1792, and the main entertainment was musical. There were parades and walks and food could be served in small painted booths. From 1745 the Musical Director was Dr Thomas Arne (1710-1778, composer of Rule Brittania) and there was a statue of George Frederick Handel (1685-1759) by Roubiliac, the plinth for which is just visible on this bowl though Handel seems to have disappeared. The Spring Gardens at Vauxhall were immensely popular and ever yone visited them. In 1786 one celebration attracted crowds of 61,000 and the gardens featured in books, diaries and memoirs. Tobias Smollett’s Humphrey Clinker (1771) describes a visit: “...a spacious garden, laid out in delightful walks, exhibiting a wonderful assemblage of pavilions, grottoes, temples... – the place crowded with the gayest company and animated by an excellent band of musick.”

The food was expensive and not of the best quality. The ham was famous: one commentator said that it was so thin that you could read a newspaper through it and another wrote that the carver could cover the whole gardens with meat from a single ham. Until 1750 most people arrived by boat but the construction of Westminster Bridge meant that people could arrive by carriage.

Apart from the main parades and the semicircles of booths, there were many quieter and darker walks. Walpole mentions The Dark Walk, Druids’ Walk and the Lovers’ Walk. These became notorious for assignations and occasional outbursts of indignation led to calls for improved lighting. Fanny Burney in her novel Evelina (1778) describes her innocent title character wandering alone in Vauxhall Gardens where she is accosted by several gentlemen who assume she is a lady of questionable virtue.

Keats wrote a Sonnet to a Lady Seen For a Few Moments at Vauxhall:

Time's sea hath been five years at its slow ebb,

Long hours have to and fro let creep the sand,

Since I was tangled in thy beauty's web,

And snared by the ungloving of thine hand.

At first glance it is not clear why these two very different places should appear together on a bowl made in China. Yet they present two sides of the same ‘polite and commercial people’ of the Eighteenth Century. The vast increase in wealth and the extension of global horizons of that century led to a pursuit of pleasure that is exemplified by the Vauxhall Gardens and which is accompanied by a change in sensibility that could no longer leave babies to die on the streets of London. Both of these enterprises are wound tightly with the cultural and artistic endeavours of the day – and their participants include creative geniuses such as Hogarth and Handel. They were also both prime sites for the display of visual art and many artists had work displayed at both sites, especially Peter Monamy (1681-1749) and Francis Hayman (1708-1776), the latter being responsible for the mural painted at the back of most of the dining booths at Vauxhall and a portrait of the Tyers family now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. And they have resonances in modern glamourous charity events which combine celebrity visibility with a moral refreshment or charitable ‘feelgood’.

It is not clear who ordered these bowls though it would have been a small order (less than half a dozen have been recorded) and the Mansion House Bowls may well have been intended as companion pieces. Maybe a Lord Mayor or rich Alderman in the 1790s selected the views and placed an order.

References:

- THARP, LARS (1997) Hogarth's China, p110, another example of this bowl and an interesting discussion of the two places.

- BUERDELEY, Michel (1962), Porcelain of the East India Companies, p191, Cat 179, a punchbowl with a view en grisaille of a London Hospital but dating from c 1750; p108, fig 77, this exact punchbowl, described as showing the Palace of Versailles (!) and with provenance: Ex Marcussen Collection.

- HERVOUËT, F&N & BRUNEAU, Y, (1986) La Porcelaine Des Compagnies Des Indes A Décor Occidental, p244, No 10.22, this same bowl, still described as Versailles!

- HOWARD, David S. (1994), The Choice of the Private Trader, p202, No 235, another example of this bowl.

- HOWARD, DS & AYERS, J (1978) China For The West, p268, No 265, the related punchbowl with views of the Mansion House and the Ironmongers’ Hall.

Sold GBP 55,000 to the Foundling Hospital Museum

Article written by Will Motley, extracted from Cohen & Cohen 2005, Now & Then